See also Aldon Morris, Michael Schwartz, and José Itzigsohn, “Racism, Colonialism, and Modernity: The Sociology of W. Itzigsohn and Brown, The Sociology of W.This claim about Du Bois’s alleged “intersectionality” stands in some tension with the authors’ claim that Du Bois centers race and racism, as opposed to class, in his work (e.g., 1). Du Bois: Racialized Modernity and the Global Color Line (New York: New York University Press, 2020), 80–2, 219.

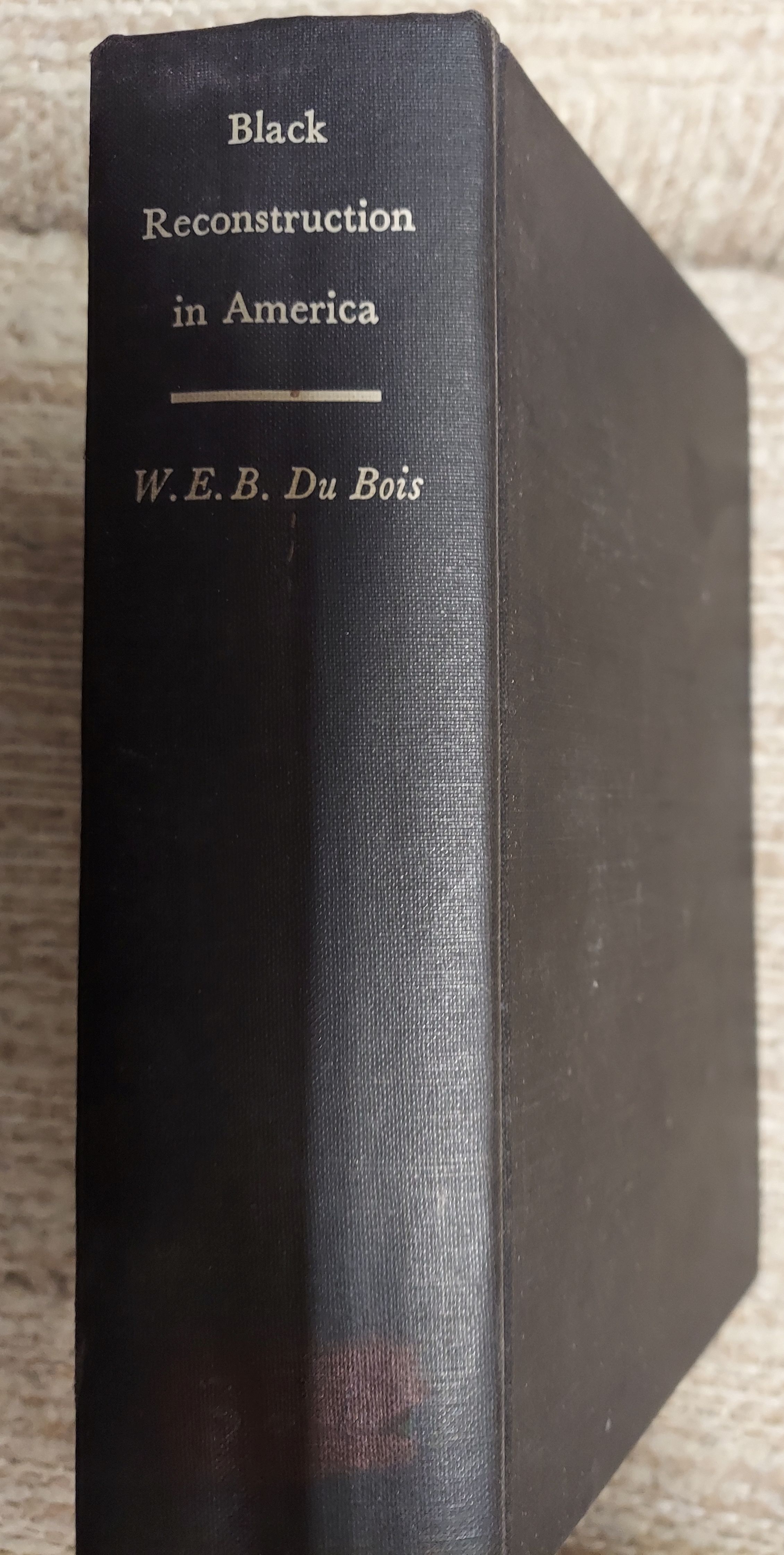

Du Bois: Black Radical Democrat (Boston: Twayne, 1986) Manning Marable, “Reconstructing the Radical Du Bois,” Souls 7, no. Gerald Horne, “Abolition Democracy,” Nation, May 3, 2022. More recently, however, Horne has emphasized the Marxist character of Black Reconstruction. Du Bois and the Afro-American Response to the Cold War, 1944–1963 (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1985). Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983), 207, 228. Du Bois and the Critique of the Competitive Society (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2019) and Reiland Rabaka, Du Bois: A Critical Introduction (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2021), esp. Du Bois: Revolutionary Across the Color Line (London: Pluto Press, 2016) Andrew J. Du Bois and the Century of World Revolution (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2015) Bill V. Du Bois and American Political Thought: Fabianism and the Color Line (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997). The best study of Du Bois’s thought prior to his Marxist turn is Adolph L. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (Chicago: A. Reed, Toward Freedom: The Case Against Race Reductionism (New York: Verso, 2020), chapter 1. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 630.Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880 (New York: Atheneum, 1992 ).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)